The old world is a ghost in Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses,1 a ghost that calls to John Grady like the moon calls to a wolf, and he must answer with the voice of all those who have gone before him, all who have ever been. His is the last cry of a species near extinction.

The dream and the draw to Mexico is work, the kind of work he did on the ranch his grandfather lost by dying and which his mother doesn’t care to save.

The first turn of adventure comes when a storm hits as he and Rawlins are drunk on something unidentifiable, perhaps fermented cactus juice. Blevins flees the family fate of dying by lightning and loses everything but his underwear.

The boys grow sick, and the horses are bemused by the sound of their bodies expelling the poisons that so pleased them only hours ago:

By dark the storm had slacked and the rain had almost ceased. They pulled the wet saddles off the horses and hobbled them and walked off in separate directions through the chaparral to stand spraddlelegged clutching their knees and vomiting. The browsing horses jerked their heads up. It was no sound they'd ever heard before. In the gray twilight those retchings seemed to echo like the calls of some rude provisional species loosed upon that waste. Something imperfect and malformed lodged in the heart of being. A thing smirking deep in the eyes of grace itself like a gorgon in an autumn pool.

The paragraph ends with a simile described by another simile, something I can’t remember ever seeing before—and what I’m made most to think of is Gollum from Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It’s a fitting image. A fitting sound.

One of McCarthy’s tics is the vague simile, and on days when I’m impatient and not particularly bright, I could describe it as lazy. I would be wrong. He uses this vagueness on two occasions that I’ve noticed, and he uses them with meaning.

First, it’s part of his habit of contrasting violent or otherwise bombastic content with a mundane simile. (He then contrasts mundane events with violent or otherwise bombastic similes.)

Second, and this is the use here, he makes comparisons to creatures drawn up from the beginnings of the world, creatures without a name, and in doing so, he points out those primal and primeval parts of ourselves. In an interview (perhaps the one with Oprah?) he speaks of the unconscious as being older than language. That’s not a one-off idea for McCarthy; he’s obsessed with these ancient aspects of ourselves.

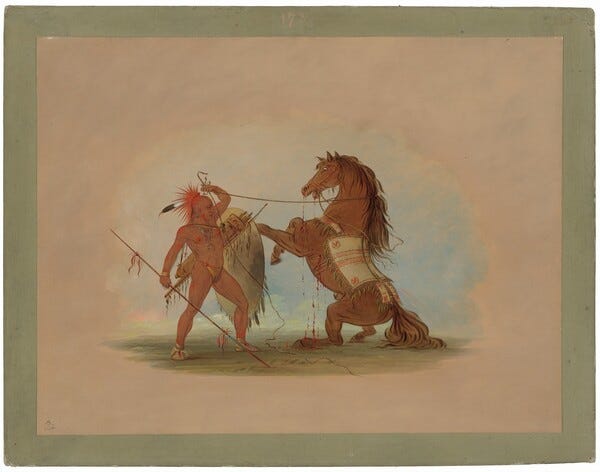

It’s an obsession that’s at the heart of this novel, for John Grady doesn’t see the ghosts of cowboys and ranch hands. He sees the spirit of the Comanches walking the old Comanche road, and that’s not a past he lost. What he mourns is the life which was made possible by stripping theirs away. The Comanche represent themselves but also all things lost and ancient. They are of the First Nations, the first people, and anything that came before them came without witness. Without names.

Let’s talk about Cormac McCarthy.

But first, let’s take care of some business—in 4 parts:

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

Every Section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

For example, you may not be subscribed to my re:write series. Or you may be subscribed to it and not want to be. The plan for the immediate future is to publish four to six times a week.

Sundays are dark.

Mondays are currently for the sci-fi serial Warp & Woof.

This week, Tuesday was the Re:Write entry.

Wednesday was a Substack Authors entry from the Champion series, where a Substack fiction author recommends another author on Substack.

This Thursday, this Re:Read essay posts in the evening.

This Friday will be dark.

This week, Saturday is yet undetermined. Last week is was Re:Write with a study of a piece of fiction from Substack to draw lessons from it about how to better write action.

To choose which of these series come to your inbox, go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Book Club Reads

Mystery, Thrillers, and Suspense

Adventures in Sci-Fi and Fantasy2

Treasures of Darkness3

Books for Children4

Tales of Terror5

All Things Creepy6

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only.

Now let’s read All The Pretty Horses.

Cormac McCarthy’s style is to some degree a solution for conveying his story with his desired lack of punctuation. The missing quotation marks is the most obvious choice, but if he could, he’d be rid of everything but the period. Even so, occasionally he finds use for a comma:

The horses stepped archly among the shadows that fell over the road, the bracken steamed.

I find the example ironic, as it’s a comma slice. Normally, McCarthy would combine the two independent clauses with an and while omitting the customary comma. I yearn to find the purpose in reversing his normal stylistic proclivities here.

It almost feels like an oversight rather than a choice, especially since it’s immediately followed by the phrase “bye and bye”. I’ve tried to look up that spelling as an alternative to “by and by”, but I’m finding nothing to support it. The comma, however, shows its intentionality in the context of the full paragraph.

These descriptions come just after the rain, when Blevins is left with nothing but his hat and his underwear:

Rawlins turned his horse and set off slowly down the road. They followed. No one spoke. After a while John Grady heard something drop into the road and he looked back and saw Blevins' boot lying there. He turned and looked at Blevins but Blevins was peering steadily ahead from under the brim of his hat and they rode on. The horses stepped archly among the shadows that fell over the road, the bracken steamed. Bye and bye they passed a stand of roadside cholla against which small birds had been driven by the storm and there impaled. Gray nameless birds espaliered in attitudes of stillborn flight or hanging loosely in their feathers. Some of them were still alive and they twisted on their spines as the horses passed and raised their heads and cried out but the horsemen rode on. The sun rose up in the sky and the country took on new color, green fire in the acacia and paloverde and green in the roadside run-off grass and fire in the ocotillo. As if the rain were electric, had grounded circuits that the electric might be.

The paragraph ends with another interesting comma choice, and with it I find my best argument for both being intentional. Neither are traditionally grammatically correct, nor in keeping with the McCarthy tradition. This latter example is entirely nonsensical on its own and requires the context of what came before it for the brain to construct meaning: with the sun rising after the night’s rain, fresh and vibrant colors burst upon the landscape, as if the rain were electric and the flowers and leaves were themselves colored lights.

It’s twisted to please his poetic ear.

We find here, too, an example of the partial repetition he’s so fond of with “green fire” then “green” and then “fire”, each describing colors of the trees, grass, and flowers.

We return to the nameless with the birds impaled upon the cactus, and McCarthy creates a metaphor with his verb choice. To espalier is to train a tree or shrub to grow flat against a wall, and these birds have been trained to grow against the cactus, frozen in a dead mimicry of flight.

See what other essays I have to offer:

“A moderate level of… constraints… frames the task as a greater challenge and… motivates experimentation and risk-taking.”

Acar, O. A., Tarakci, M., & van Knippenberg, D. (2019). Creativity and Innovation Under Constraints: A Cross-Disciplinary Integrative Review. Journal of Management, 45(1), 96-121.

The irony of style is that given the full breadth of the language’s possibilities, we tend toward what we’ve comfortably used before. By artificially restricting her choices, an author can force herself to see new possibilities.

One function of the comma is to replace a conjunction. Without it, McCarthy turns to other solutions:

John Grady started to reach in his pocket for a match and then he rose and walked over to the workers and squatted and asked for a light. Two of them produced esclarajos from their clothes and one struck him a light and he leaned and lit the cigarette and nodded. He asked about the boiler and the loads of candelilla still tied on the burros and the workers told them about the wax and one of them rose and walked off and came back with a small gray cake of it and handed it to him. It looked like a bar of laundrysoap. He scraped it with his fingernail and sniffed it. He held it up and looked at it.

The heavy use of the conjunction, and, within the sentences is called polysyndeton. Ironically, a Hemingway-like lack of connection between the sentences has been noted, which would be parataxis. I never would have thought the two techniques could be used together and so missed the parataxis and had to have it pointed out to me.

These men see the young Blevins riding with them in his underwear, and they ask to buy him. It’s a stark contrast to the hospitality that’s met them otherwise and a reminder of the dangers they face in this adventure. On the heels of that reminder, they ride into town and quickly spot Blevin’s missing revolver and soon after find his horse. Blevins, young and impulsive, steals the horse back, and the boys escape separately, parting ways with Blevins for now, just before finding both the ranch where they’ll work and the girl who captures John Grady’s heart.

We get into John Grady’s head more than we do the kid from Blood Meridian, but that interiority doesn’t extend far. It enables us to share in his vision of the Comanche, but for the most part, Rawlins serves as the foil whose character highlights John Grady’s by contrast.

The End of Chapter One

I believe these are some pretty good old boys, whispered Rawlins.

Yeah, I believe they are too.

You see them old highback centerfire rigs?

Yeah.

You reckon they think we're on the run down here?

Aint we?

Rawlins didnt answer. After a while he said: I like hearin the cattle out there.

Yeah. I do too.

He didnt say much about Rocha, did he?

Not a lot.

You reckon that was his daughter?

I'd say it was.

This is some country, aint it?

Yeah. It is. Go to sleep.

Bud?

Yeah.

This is how it was with the old waddies, aint it?

Yeah.

How long do you think you'd like to stay here?

About a hundred years. Go to sleep.

They’ve come hunting for the life that was lost, and this conversation confirms they’ve found it. This is their idol and ideal.

To clarify who is speaking, little of which is clarified, McCarthy graces us with a colon, but otherwise the closing dialog is simple and uninterrupted.

The contrast between the narrator’s diction and that of the characters is another regular trait, and I argue that it’s his contrasts which make McCarthy so readable. As a writer, it’s the main lesson I’ve taken from him because so much else that we might borrow, we’d be in danger of using in shallow imitation, but that sense of contrast highlights and reveals opposing styles, much in the way that Rawlins reveals John Grady. It keeps the story interesting and the reader engaged, acting the way colors do in art, guiding our eye and ear, teaching us what’s important and tending our challenged attention spans.

The masculinity and violence of his works are certainly a draw for many of his readers, but while McCarthy has a reputation for being inaccessible because of his punctuation, I believe the accessibility created by his dedication to contrasts helps readers find and embrace those aspects of his writing they love so dearly.

— Thaddeus Thomas

New! Weekly Flash Fiction for Paid Subscribers—these won’t be emailed to you, but you’ll find the link in my regular posts. Here’s a tiny piece of horror: No One to Blame.

The Pretty Horses Thus Far:

Philip Meyer and Cormac McCarthy: The Son and All the Pretty Horses—the first literary analysis essay compares the work of Philipp Meyer and Cormac McCarthy and chooses one for the first read along.

The Secret of Style: Part 2 — from the prose style series, I take a look at how Cormac McCarthy teaches us the secret to a successful prose style.

The First Pretty Horse Ain’t So Pretty — a critical examination of the book’s first sentence.

The Second Pretty Horse Rides an Alien Shore — an introduction to me as a reader. Plus, John Grady and the others enter Mexico.

The constant temptation to call this book All My Pretty Ponies!

Any visitors from this link are attributed to Marian L Thorpe

Any visitors from this link are attributed to Larry Hogue

Any visitors from this link are attributed to Mark Watson Books

Any visitors from this link are attributed to M.P. Fitzgerald - Graphomania

Any visitors from this link are attributed to Iseult Murphy