Warp and woof (warp and weft): (from dictionary.com) The essential foundation or base of any structure or organization; from weaving, in which the warp — the threads that run lengthwise — and the woof — the threads that run across — make up the fabric.

But let’s take care of some business first—in 4 parts:

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

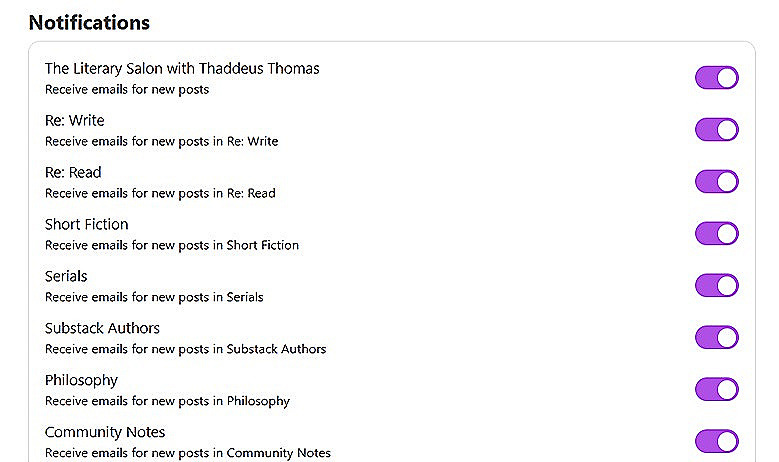

Every section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

That’s https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Visit the Totally Awesome but Very Humble Authors promotion.

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only, check out the Subscription Specials:

Or subscribe for free:

To purchase a subscription, you’ll need to visit my site. That function no longer works directly in the app.

And now the second chapter:

Warp & Woof

Chapter Two:

Cтрелки

(The Strelki)

Galina / Warp

Dogs give birth in litters.

Doctor Galina Popov waited patiently as this point was repeated by the ship’s head of the fauna sub-section of Ecological Sustainability. Dogs give birth in litters, but Pervoye Strela, like all the Strelki, did everything within constrained measures; the minimal resource consumption for the maximum output. The concept of bringing forth a dog, with all its consumption and waste, could only ever mean one dog—two if the replenishing of embryos was in mind—but if Doctor Popov recommended the birth of comfort animals to nurture the healing process for the Tret'ya disaster survivors, that meant multiple people receiving dogs of their own; that meant a litter, and they could reproduce the family linkage integral to a litter by selecting embryos from a single mother, sired by a single father. All this meant that in the fullness and completion of time, a miracle had come upon them. Pervoye Strela could house a true family-unit of dogs.

“Just one,” Dr. Galina Popov said. “The others declined.”

Declined. How does one decline a dog?

Galina could answer that question, but she couldn’t really understand. Not really. Under normal circumstances, anyone born to a Strelki generational ship would delight in something so common to Earth and yet so exotic. The birth would rocket the dog’s owner to stardom and envy, inducing something akin to class in a nearly classless society. To have a dog was wealth beyond measure and a link back to a heritage lost, and yet, these were not normal circumstances. A dog could offer a survivor a myriad of gifts, but she couldn’t give back what was lost, and if she represented the possibility of healing from that grief, most survivors wouldn’t allow it. The price for survival was pain, and the mythical concept of a dog’s love for her human threatened that pain. Thus they said no, everyone but Oleg Tereshkova, the one who called himself Warp.

“Help me understand,” she said in one of their sessions. “That name is the reason you broke Dmitri’s nose, and yet you’ve adopted it for yourself.”

“Now,” he said. “Here. After.”

“You no longer want to be Oleg?”

“Everything we were is gone. Changing names is just a refusal to pretend otherwise.”

Like the others, Warp protected himself against the threat of healing, but unlike them, he couldn’t refuse Laika. On Tret'ya Strela, he’d been the head of the fauna sub-section of Ecological Sustainability. From the embryonic samples Zasha had kept viable, he brought a precious few to life, but never anything so grand as a dog. The implications of the offer resonated far too deep to be ignored, but even then he could only go so far. She had to choose the breed for him, a Chocolate Labrador; she named her Laika, after the first dog in space, but when the task she could not take on his behalf was to love her. On the day Galina delivered the puppy to his apartment, Warp crumbled to his knees and wept his mother’s name.

“Tell me about your mom,” she said in another of their sessions.

“Every human consciousness,” he said. “Can you imagine?”

“Imagine?”

“My mother asked me that, and I answered, ‘Every human on Earth.’ The fear was always that they’d build faster ships and beat us to an inhabitable planet, but in the end, they found a way to never leave. Then she asked me if I liked my soup; and I laughed, and she laughed with me. What else could we do?”

Within giant computers in the methane seas of Titan, the consciousness of every man, woman, and child left on Earth was now stored. The descendants of those the Strelki left behind—they’d become immortal.

“I’ve heard no such news,” Galina lied.

Warp explained. In the life they’d once known, Dmitri Afansyev had been head of communications. Aboard Tret'ya Strela, that meant inboard communications. The flagship, Pervoye, tracked the interchange with the drones sent to the new planet, and the flagship also took messages from Earth and determined what responses they alone would broadcast back to some distant generation.

But Dmitri had listened; what Pervoye would not tell, Dmitri shared in whispers.

In the armada of generational ships, they had grown up with an abstract awareness of three others, but one ship they had known in all the intimacy, awareness, and imperfection of home. Within that imperfection, Dmitri became a legend.

“You heard about Varp-i-Vol’; yes?” Warp’s mother asked over dinner, speaking in hushed tones and casting sideways glances about their apartment. She was a chief starshina, the second-in-command of engineering, and she had only heard about the communication through rumor.

Warp sighed, and her eyes widened.

“This is why that boy calls you Varp?” she asked.

Warp awkwardly shrugged his left shoulder. His right arm rested in a sling, and bandages covered his busted knuckles.

“Everyone forgets soon enough.” She was a tall woman, powerful and intelligent, but she was still his mother. She believed in things simply because she thought her son deserved them. Reality be damned.

Doctor Galina Popov tapped her screen, noting the time; she would have to report this to Command. It seemed irrelevant now, this breach of protocol, but that wasn’t her call to make. She studied her patient as he sat in what was rumored to be the comfiest chair in the fleet. It engulfed him like a womb. She wondered if the imagery had occurred to him, a womb; probably not; men didn’t take comfort in such ideas. She encouraged him to continue.

Exhausted, Warp dropped his spoon into the empty bowl, and his mom watched with a mixture of compassion and judgment.

“You shouldn’t have hit him,” she said. “It’s a term of endearment.”

The English name for the Titan program, Warp and Woof, was an idiom for a thing in its entirety, literally: a fabric’s underlying structure. The Russian transliteration was Varp i Vol’, and vol’ was similar to the word for an ox. As the ship’s animal wrangler, nicknaming him Warp was the crew’s way of dealing with yet one more thing they’d lost when their ancestors began this journey.

Warp should have taken it better. He knew that.

In keeping with tradition, a rug hung on the wall beside their little table. A flower-patterned wallpaper covered the rest of the apartment; it meant home to them.

His mom pushed aside her bowl and poured them both a glass of Nastoiki. It tasted of fresh-plucked plums.

“Ambient hydrogen levels are still elevated.” She placed her empty glass on the table with a flourish.

“No identifiable source?” He poured.

“Nothing good.” She held her drink, pondering its faint hues. “I want you to apologize to Dmitri.”

“Mom.”

“Bring him here for dinner, alone. Promise me.”

“Just let it go.”

“Command looks the other way when he gossips about news from Earth, but they will keep him quiet where it matters, especially if such news could cause a panic.”

“What news?”

“There are things happening on this ship. Convince Dmitri to come. No wife. No child. Just him. Tell him you want to mend your relationship.”

“And then what?”

His mom put away the bottle and shuffled off to her room. Her shoulders sagged beneath an unseen weight, but when she spoke, Warp heard only determination. “We make him talk.”

Doctor Galina Popov tapped her screen. Warp believed Command had known about the threat and yet said nothing. For a moment, she considered the possibility of keeping this news to herself, but if the other survivors believed the same, the secret wouldn’t last. Word would spread; belief in Command and in this ship, their home, would crumble; the trust that underpinned their society would fail.

#

Warp’s breath felt flammable, ready to bellow destruction from his chest. He was no longer Oleg Tereshkova but the great dragon, Zmei Gorynych, devourer of the sun.

Warp’s mother slammed her glass on the table; Dmitri matched her without hesitation, but Warp pushed his glass away, complaining that his teeth were numb.

His mom poured new shots for Dmitri and herself. “The ambient hydrogen levels are elevated.”

She drank.

Dmitri followed her lead. “So?”

She poured again. “Hydrogen plays many roles on the ship. It’s laced into the very materials. It’s fuel for the pulse engines.”

Dmitri eyed his glass, and when Warp’s mom downed hers, he didn’t rush to follow. He looked to the door and then at Warp, who was fixated on the bruising around Dmitri’s eyes.

“In either case, it’s a shield against cosmic radiation,” Warp’s mother continued. “What have you heard?”

He stammered. “I can’t.”

“I’m Engineering’s second-in-command,” she said. “Don’t you think I should know?”

“If it proves to be significant, we have time to evacuate.”

The bottle fumbled in her grasp, almost falling. “Evacuate?”

Dmitri’s face flushed. “I didn’t say anything.”

She turned to Warp, her skin the color of ash.

“Mom?” His voice sounded like a child’s.

“Embryology,” she said. “The shielding is doubled there because of the fragility of the specimens. I’ll have your work routed through their systems, your wife’s as well, Dmitri. You’re both to live and work there until I get this thing figured out. Your child, too, Dmitri. I’m serious about this.”

“But Command…” Dmitri’s argument drifted off.

She slammed her fist into the table. “If secrecy is so damned important, they’ll do as I say. You’re moving there tonight.”

The ship contained vital areas within redundant shielding, a chrysalis, into which one entered by way of an enclosed turnstile. That night, Warp, his mother, and Dmitri passed through the first turnstile to enter the outer ring of the embryology department. The faces of those working swam within Warp’s vodka-impaired vision. As they approached the second turnstile, someone offered a mild objection which his mother’s credentials silenced.

They moved within the massive wedge, surrounded by walls as black as the void, and entered the inner chrysalis. Zasha and her team looked up from their work, startled at the intrusion.

“Bring the rest of your team inside,” his mom ordered, ignoring the realities of rank. “All in, including your families. I’ll send you a few more.”

“What is this?” Zasha demanded.

“Command doesn’t know it, yet, but this is an evacuation.”

“You’re drunk,” Zasha said.

“In vodka, veritas.”

His mother kissed him as Zasha watched, Zasha’s wide and chiseled face rigid with the shock of their intrusion. Warp wasn’t thinking about the danger. He wasn’t worried about his mother heading back beyond the shielding. He was none of the things he should’ve been; Warp was only embarrassed.

His mother was going back out to face a threat only she understood, and he pulled away, ashamed.

Dmitri followed her to the turnstile, but she held him back, promising she would send his family. Then she was gone.

“This is a clean area,” Zasha said in protest.

Warp couldn’t look directly at her. She wanted them out, and he wanted to run. She was older, powerful, and betrothed, but most of all, she was beautiful with a quality of self he’d never experienced in another. Her presence took up a room. The idea that she had an opinion of him made him tremble, and the possibility that she thought ill of him was worse than any death the universe could bring.

The soft rumble of the turnstile stopped, and he knew his mother was entering the outer ring, where Zasha’s fiance worked.

“Get out,” Zasha said.

“You should bring the others in,” said Dmitri.

Later, they’d report that Warp moved to the turnstile and triggered its return with the intention of rescuing the others. He never admitted that, in truth, he was only trying to leave.

The floor rumbled, and they looked at one another. Warp hoped the vibrations came from the turnstile’s movement. Time became uncertain, at least in his memories and maybe in the moment. His mother was still in the outer ring. She would have known what the rumbling meant and warned the others to flee. If they’d delayed at all, then perhaps Warp’s actions meant nothing, and he knew his mother’s nature, she’d have been the last one out.

Later, Warp diagrammed everyone’s position and timed the distance. Counting from the end of the first shock, even granting an additional second before she responded, they had time enough to enter the wedge, time enough for the turnstile to begin its revolution and seal off the gap.

In his heart, Warp knew he’d killed them, and every night, he told himself it didn’t matter. The Tret'ya had no survivors.

—Thaddeus Thomas

New Subscribers and Transfers from my Author Site

You may not be subscribed to everything you want from me:

Toggle your choices at https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

Discover my essays here:

And don’t forget my short fiction.

Interested in another serial?

Looking for more fiction writers on Substack? I’ve started a list of recommendations:

Every time I read something from you, whether fiction or not, there’s this warmth that emanates from the writing. As if the letters, your voice and one as a reader were suspended in this atemporal bubble, existing in harmony. I hope it doesn’t sound lame or whatever, but, you’re someone I’m starting to look up to.

Thanks for doing what you do.