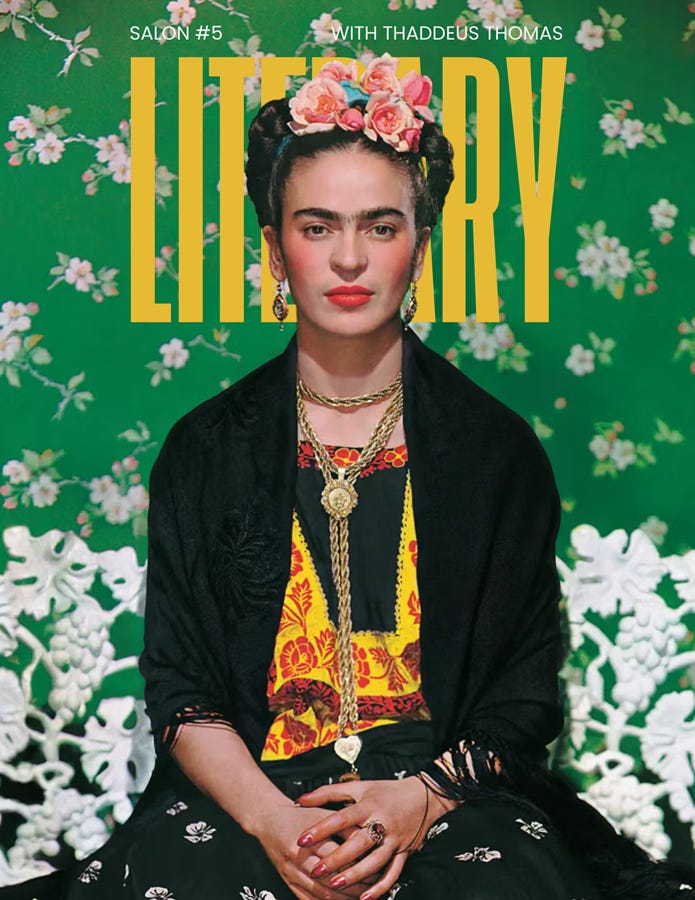

Literary Salon #5

A Substack Week-in-Review

In Response To A False Dichotomy

See “In the Stacks” for the link to Emil Ottoman’s response to my article from issue #4

I’ve got one problem with your article, Emil, and his name is F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Even among the non-professionals who are surrounded by the terms plotter and pantser, there’s a growing understanding that we’re dealing with a spectrum, not a binary. If that’s true, and if the terms are unwelcome in professional circles, we need to question the source of their popularity.

…the terms in question serve a tribal/motivational function. They help writers align with other writers who share their frustrations or success. And they can be useful for building community and framing advice, not deep literary critique.

— Emil Ottoman

All these reasons are true, but I think we mostly gravitate to the terms in self defense. Now, it would be easy to point to all the contemporary slings and arrows thrown by these self-described sides, but we can look back to the great writers and find the same one-sided thinking:

“You don't write because you want to say something,

you write because you have something to say.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald

F. Scott right to hell!

There are many of us who sit down to a blank page to discover what’s in our minds. We want to say something and have no idea what it is. We’ll have something to say once we’ve said it.

The false dichotomy exists to fight the false unified-field theories of how writing works.

There are other approaches to revealing the lie behind these claims, of course. We could admit that the greats waged theatrical battles against one another because it was good for business—and sometimes because they really were full of themselves.

One of my favorite examples was Balzac saying that Victor Hugo’s fatal flaw was a failure to connect his books into a shared universe, the way Balzac had done. Yes, two hundred years before the MCU, we had the BLU—the Balzac Literary Universe.

And Victor Hugo’s failing as a writer, according to Balzac, was not being Balzac.

Hemingway and Faulkner waged war over style, and I don’t believe a word of it. That doesn’t mean the war wasn’t important. It defined literature for the twentieth century—but it shouldn’t have. They created a false dichotomy of themselves and trapped those they inspired within it.

You don’t usually see me use the terms plotter and pantser because I intentionally avoid writing about process, but I was asked to write the article. It was ultimately rejected because they didn’t think it was actionable. They were probably right, too. I’m not drawn to actionable items, like world-building challenges: “What do people in your world do with their expelled feces?” I know exactly what they do. They throw it at questions like that.

Mind you, there’s nothing wrong with that process. I partner with a master world-builder for the Open-World Stories project (Haly, the Moonlight Bard ✒️) and she probably loves that stuff. I don’t.

Why not?

Because for me nothing exists beyond the written page. You can’t ask me definitive questions about story facts beyond what I’ve written. I might have ideas, but I don’t know any better than you until something is locked on the page. There is no truth beyond the prose.

That’s not the only way, but it’s my way. It’s my thinking, and my process is whatever pulls a story from this brain and puts it onto that computer screen.

We build walls to protect our right to think the way we think—the right to use our brains and not someone else’s to write our stories.

The disrespect and slander certainly started before the great divide, but it’s only worsened since then. The tropes associated the mythical plotter are easier to teach because they’re actionable, and so those who hawk such lessons deride any other approach.

Not only did I buy into the dichotomy, but for a while, I agreed that being a plotter was better—even though that wasn’t me.

And that’s where I come back to Emil’s challenge. Get rid of the terms? Cast them from your vocabulary? It’s fine to desire such a thing, but unified field theories persist. In ridding ourselves of the terms plotter and pantser—by insisting that we are all just one thing, writers—we render our young compatriots defenseless.

We need to maintain the defensive wall.

The spectrum idea still maintains the terms, and Emil’s challenge is to banish them. He may also have given us the replacements we need.

The most common entry points to story are heuristically in rough order character/ premise/situation>image/scene>and finally title or formal form.

—Emil Ottoman

That resonated with me. I vividly remember coming up with the title for The Sphinx and Ernest Hemingway, which was the entry point for that particular story. The order of the terms were originally switched, Ernest Hemingway and the Sphinx, but whatever story that would have produced held no interest for me. When I switched the terms, however, I immediately knew I needed to start writing.

I’ve learned to call myself a metamordernist because I’m drawn to writing stories that emerge from other sources, whether its history, literature, or a Biblical retelling using Winnie-the-Pooh. Often, my way into a story is the material that inspires it. My current novel WIP grows out of real diary written by an American nurse in Liege at the beginning of World War I. Kraken in a Coffee Cup grew out of the text of Moby Dick. I could correctly say that The Sybiliad grew out the role Florence played in the effort by Constantinople to save itself from the Ottoman Empire by bridging the gap between them and the church of Rome, but the entry point of entry points for that story was really the politics of gardens in pre-Revolutionary France and Renaissance Italy, even though that aspect doesn’t present itself in the story.

If we’re no longer identifying ourselves by an allegiance to a false dichotomy of processes, we can turn to the various entry points as different ways of approaching any particular novel. We may have our favorites, but we’re not excluded from any of them. Moreover, any system that demands allegiance to one entry point might be useful when we’re using that entry point and otherwise ignored.

Ignored right to hell. F. Scott and his Fitzgerald!

—Thaddeus Thomas

Literary Salon #5

A comment from Corey Evans regarding my upcoming book: Deeper Stories. “This section [on sentence length] might be the best piece on the craft of writing I’ve read in any trade book.”

Now is the perfect time to commit to a new relationship with the Literary Salon.

Not a subscriber? Subscribe at no cost.

Already a subscriber? Become a paid subscriber at a huge savings.

Already a paid subscriber? Become a True Fan and help me keep those discounts going for writers and readers on a tight literary budget.

A note to email readers: this magazine concept only works if you allow yourself to click on a link and leave the email. If you’ll make the commitment to do that, I’ll do everything I can to make it worth your time and effort.

Looking for a fresh new Author Newsletter?

Find a new author and get a book as a welcome present.

Today’s Reading

Headline Article:

In Response To A False Dichotomy

In the Stacks:

Reviews / Duck Commentary:

The Epilogue Saga: A Shiedbreaker Review (by 5 ducks in a trench coat), Zani D reviewing Tom Schecter’s Shieldbreaker

Fiction: horror to make you guffaw

Essays

Craft Pathology: Pantser? Plotter? Paraphilia? by Emil Ottoman: An Essay in Correspondence with my Literary Salon #4: Re-Imagined Plotter Tools

From the Literary Salon:

For Readers:

The Last Temptation of Winnie-the-Pooh. Chapter Four. Based upon the works of and including passages adapted from A. A. Milne. A serial.

Tom Schecter, Championed by Simpulacra

For Writers:

Programs at the Literary Salon:

The Franklin Project / Open-World Fiction: a joint venture with Haly, the Moonlight Bard ✒️

MmmFA (Mighty Fine Arts): Holding one another accountable for getting that book written. See our Slack Forum.

Reading Groups: Currently reading Empire’s Daughter by Marian L Thorpe; see our Slack Forum.

Closing Article:

Memories of Slander Past by Thaddeus Thomas (see below)

Memories of Slander Past

One poor woman was run off of Twitter for saying she’d never read a novel by a pantser. She couldn’t imagine enjoying a novel that meandered with no idea where it was going.

It’s easy to poke fun at people who believe that an approach to writing fiction will also define it’s outcome, but I know I’ve been guilty of that thinking. Mistborn bored me. The characters remained one-note for too long, becoming monotonous before they finally reached a point where change could begin. I blamed it on plotting, assuming Sanderson had designated that the character would feel a particular way until a plot event initiated the change. A pantser, I thought, would have been able to allow the character to evolve en route to the bigger change, without being locked into the limitations of a preconceived plot.

More recently, I told Marian L Thorpe I could feel her plotting in the best sense of the word, only to learn she hadn’t plotted at all.

The examples I used in the original essay were, as Emil suspected, pulled from personal experience, and when I mentioned teachers hawking a method, I was thinking of one particular teacher I eventually had to block on Twitter.

That stuff eats at your soul.

There will always be slander, even if we put to rest the use of these terms forever. Being a writer is hard. There are no guarantees, and much to the contrary, the odds are against our success. To psychologically guard themselves against the uncertainty, people cling to false promises. They find arbitrary ways to define the “serious” writer so they can separate those who will make it (including themselves) and those who won’t.

The best we can do it embrace the uncertainty and write.

Thank you for another great week,

—Thaddeus Thomas

I am a selfish nerd, I never want this discourse to end. I am declaring, forthwith, that I am a "Kilter" and I will be gatekeeping the word as far as whimsy and boredom allow me!!

Thank you for the mention, Thaddeus!

You probably know by now that I am anti-labels (which is a label), and veer towards Emil's side. As much as I can say that I take sides.

Still, I wanted to leave a comment on his reply that the dichotomy is not itself bad, especially for writers that are just starting out on their journeys. All the decent craft advice that employed this dichotomy admitted that purism in this matter is foolish, and I think that your original piece started from this assumption. At the end of the day, they are just tools and you got to have a name for them if you are going to tell somebody else how to use them.