I write this to chronicle my thoughts on flash fiction as I read through some of the stories written for the first round of the Franklin: Open-World Fiction project. The idea is that we start with one flash fiction story, and when you’re done reading, you choose one character to follow to another story and another. The first round will reach five layers deep, and that’s where our authors have begun, with sixteen final stories.

Your turn for reading the stories will come, but for now, join me as I consider how to write flash fiction.

I am approaching these stories in a randomized order so that no one will know whose story I’m referring to at any given moment.

The article begins after a lengthy presentation on managing your account.

This article is part of Literary Salon issue #5.

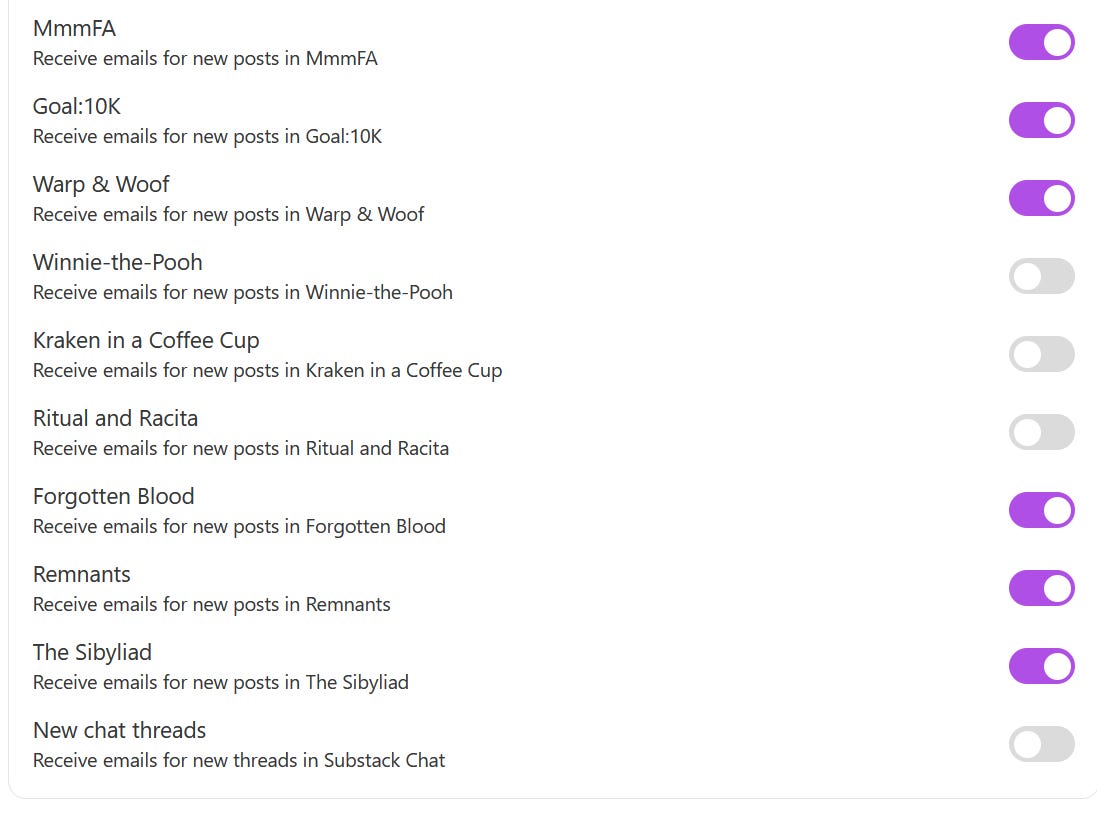

If this project is something you don’t want to miss, make sure you’re subscribed to the Open-World Stories section of my newsletter. By toggling sections on and off, you choose what emails you want to get. The top level is the magazine that includes a review of the week, so you can catch up on anything you missed.

If you’re already subscribed, there have been times when emails, intended only for the authors, were accidentally sent to you. We’re moving those posts to author site for Franklin run by Haly, the Moonlight Bard ✒️

What Emails Do You WANT to Receive?

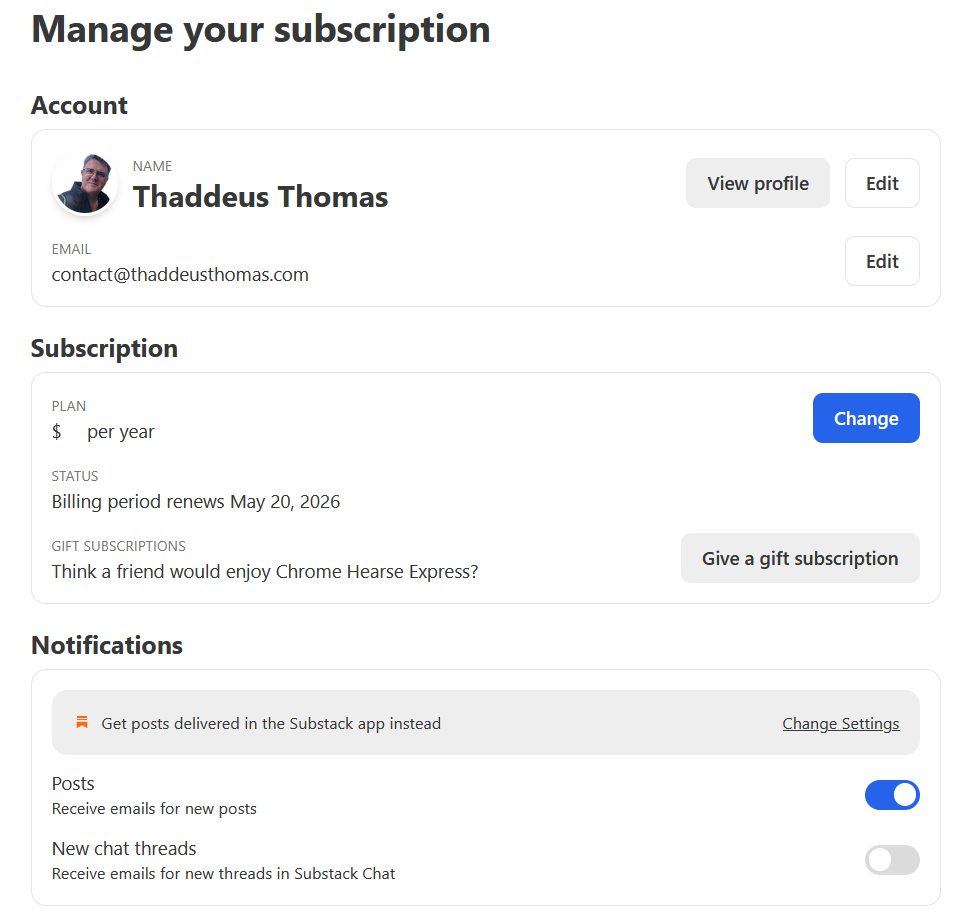

You can manage any account by typing “/account” at the end of the address. I opened mine at Chrome Hearse Express by Pablo Báez so you can see what a normal account page looks like. (Slightly edited for security reasons.)

There are no sections. You just choose if you want to receive posts and chat threads.

That’s a normal account.

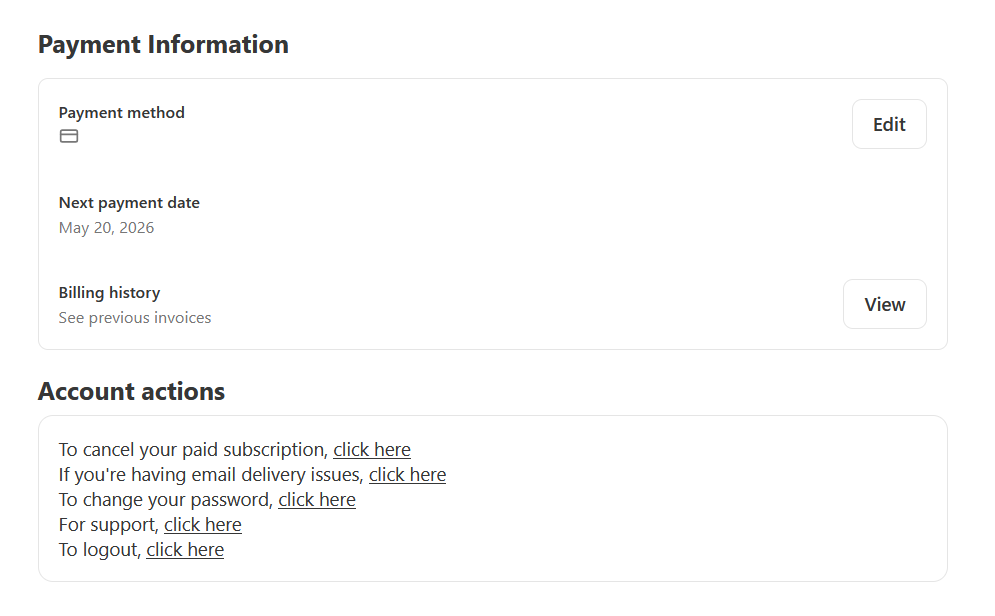

This is what my account page for the Literary Salon looks like:

The top section is different because I own the publication.

Hmm, I wasn’t aware I’m not receiving my own Games posts. (I don’t post here often, but this is where I talk about creating board games.)

You’ll notice I have a Serials toggle, and later on, the various serials have their own toggles. The Serials section is meant to be a little introduction and table of contents. They go out very rarely, but give you a chance to decide if you want to receive the new serial. I highly recommend you keep this one on.

(As the owner of the publication, my account page doesn’t include a general unsubscribe button. Only push that button if you want to stop receiving the newsletter in its entirety.)

I don’t have some of the serials toggled on because they were complete serials—but now The Last Temptation of Winnie-the-Pooh is getting a new serialization, and I’d miss it. People have responded really well to this one. Be sure to catch it.

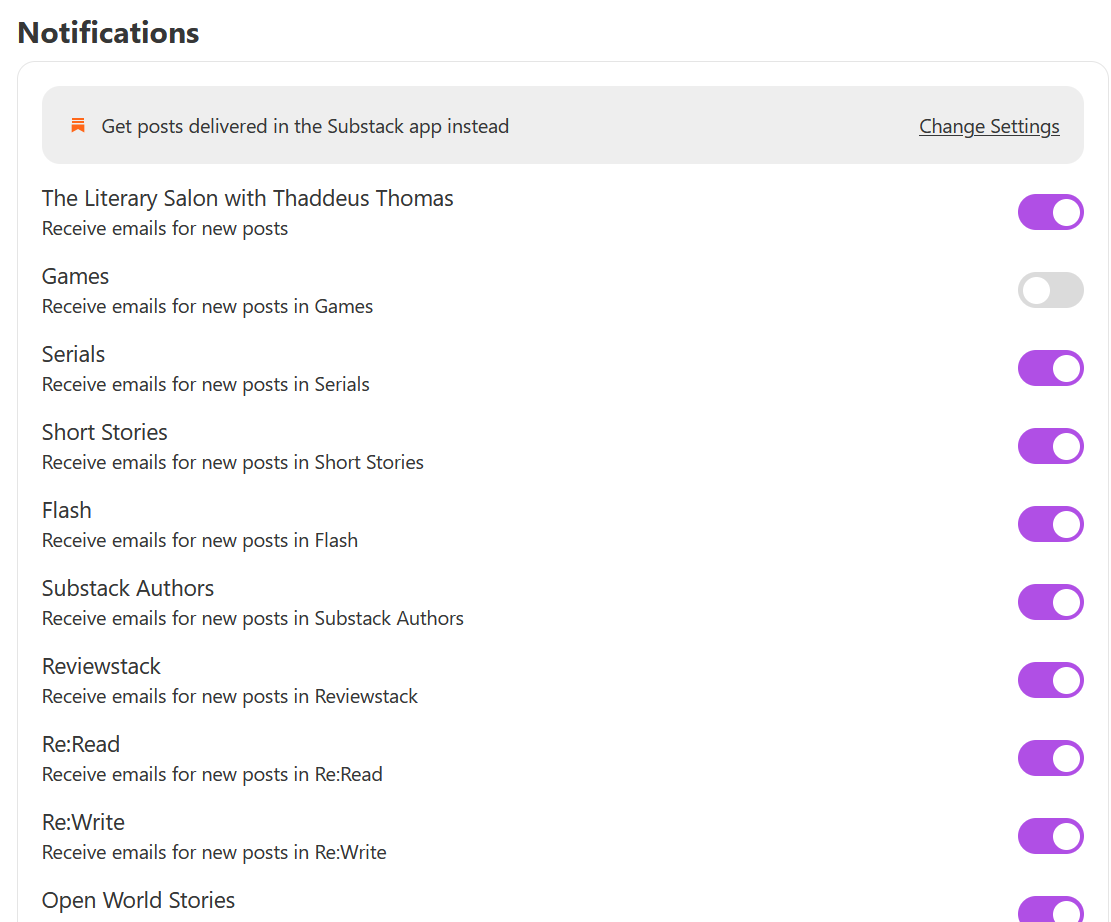

At the bottom of every account page is the following “Account Actions” box:

Pablo and I represent the two extremes. One reason I run my publication this way is because I tend to post often. You can opt-out of those emails that don’t interest you. Here are some possible variations you might consider.

Weekly magazine reader: toggle off everything but the top level. You’ll receive the magazine post weekly, on Wednesdays, 3:30am eastern time. The magazine includes original material as well as links to everything I’ve shared through the week and links to some great work others are doing.

The reader (only): If the material I produce for writers doesn’t interest you, you can receive only the reader-focused materials. You might want to limit yourself to:

The Literary Salon (magazine)

Serials

Short Stories

Flash

Substack Authors

Reviewstack

Re:Read

Open-World Stories

The serials of your choosing.

I’ll probably move where Open-World Stories falls on this list. It was originally intended as a section for the writers only, but as it is, over 1300 people are subscribed. We currently have 16 authors. We’re moving the author stuff to the Franklin newsletter, and when the first round begins, the first story will publish here. (You’ll have to follow the links to read more, choosing your own path through the stories.)

Thank you for subscribing,

Thaddeus Thomas

How to Write Flash Fiction

I love the satisfaction I get with a real ending, when a full story is told, which is really hard at this length. Twists are common in flash fiction, but they can often read like we’re being told a joke, not a story, and getting to that ending is tricky. By the rules of the game, you’re working with limited material.

One option is a dialogue heavy tale, simply told. This can run the risk of not being grounded and losing the reader in a lack of detail. Other flash pieces have no dialogue and more traditional prose. With a story carried by description, a brutal simplicity is less likely to work, and an indulgence of prose allows the reader to lose himself in the story.

Advice on flash fiction often focuses on cutting out words, and while cutting unnecessary words always works in any context, I’ve seen it taken too far. It’s been long enough that I think I’m safe in repeating an example from memory without risking the original author’s feelings.

The example was the phrase a cold wind from the north, and it was suggested that all cold winds come from the north so you can cut that phrase. So far, I’m interested. Most writing can be improved by looking for unnecessary phrases or phrases in the wrong order. Then the author went on to say that we can assume a wind is cold, so cut that, and we’re left with the simplest form: a wind.

Nope. I mean, if the character of the wind holds no importance then fine, but this isn’t great advice—at least not as illustrated. The point is to make our words count, and a snarling wind is not the same as a wind.

A cold wind is generic. A biting wind is too commonplace. Make those words count. A snarling wind suggests the noise and the threat of the bite, and it’s not something I remember reading before.

I was re-reading chapter three of The Last Temptation of Winnie-the-Pooh, and there’s a bath gag in there that relies on the old “it’s not even a Saturday” punchline. That’s a waste of words, and I’ll need to think of something else before that goes to book form.

Avoid common phraseology, but being common isn’t the worst sin. After all, it often slips by the reader unnoticed. It’s possible to make the problem worse by trying to fix it. First, don’t almost write a cliché. A near cliché is a still a cliché, only awkwardly written. Second, when we step away from the common phraseology, our original constructions can be clunky and hard to understand. We have to know what you’re saying.

I have a very brief article on figures of speech that was behind a paywall. Because of it’s potential usefulness here, I’m making it available to everyone.

Don’t confuse figures of speech with clichés. A figure of speech is a shared construction among many original statements. That common phraseology is a feature, not a bug. A near figure of speech is often just bad writing, written in a misguided attempt at originality.

For a helpful guide on figures of speech, I recommend The Elements of Eloquence by Mark Forsynth.

The first two stories I read for the project represented these two approaches. After considering what I’d read, my takeaway was that a very brief story requires that we ground the reader quickly. That way, if we have to be brutal in our economy, the reader doesn’t feel lost. Due to the brevity, it’s possible for our faults to be forgiven if the reward is great enough, but we can reduce the risk by grounding the reader well.

The third story was sweet and emotional, with no twist ending, just a resolution to the emotion of the moment. I thought something else was being set up, but it held true to the emotional core of the relationship being displayed and found no need to diverge into anything else.

I had to go back and re-read the fourth story. There’s a point in a story where it tells me what it is, and sometimes, nothing much clicks until I reach that point. I missed a few key points on the lead up, but once the story clicked into place, I was really enjoying it. Then the ending came, and I knew I’d missed something.

There are two points to make here. My missing an element can absolutely be seen as a me problem. However, it’s important to know where our stories come into focus for our reader. This is the moment that they understand the kind of story they’re reading and have an anticipation for the direction it will take. This in a point of investment for the reader, and until we have our reader invested, it’s easy to lose them.

There are other ways to hit a point of investment, and our stories can use more than one. A really interesting personality is an example. However, that moment the story clicks for a reader is the moment your reader know this is something they want to read. The characters, the situation, the stakes, and the genre become clear, and the reader straps in for the ride.

In flash fiction, that’s a long list for a very short story. These stories suggest that the most important element (outside of the ending) are the characters, their personalities and relationships. Jump right into a boldly presented personality that’s fun to explore. Give us that revelation of personality and let us see how the characters play off of each other.

Where the stories struggle, the brilliance of a character fails to shine through, and the story feels told rather than shown. I’ve written about the limits of the “show don’t tell” rule, but here I’m reminded how the problem is often in subtle word choices. When we move away from the specific to the general, we lose narrative power.

The following examples are my invention:

Several neighbors opened their doors to investigate.

That has a different feel than: Next door, Joe peeked out, just enough for me to see his scrutinizing gaze.

In my article on the rule, I made the argument for how the first example can work, but that relies on the author using the line to obliquely show us something that’s unstated. That’s not what’s happening here. It’s just a line of action, and especially when these lines follow one after another, specificity is key. Avoid group nouns and show us a specific example.

The difference is witnessing vs. understanding.

In one otherwise brilliant story, there’s much work done to make sure we understand. We’re grounded, but too grounded. We need to move into the key relationship sooner and highlight one or both personalities. The backstory should be revealed in that interaction rather than being told up front, and finally, we need language focused on the specific, not the general.

Clarity is important, but we want that clarity in what we experience rather than what we’re led to understand.

Stories with this problem remind me of an art class I had in seventh grade. We were instructed to draw a shoe, and the impulse we had to fight was to draw our understanding of a shoe. Our understanding of a table, for example, is a flat surface with four legs, and young children will draw all four legs, no matter how abstract the picture has too become to represent them all. If we draw what we see, the table or the shoe is simply the object before us. We draw that—not everything we know the object to be.

As Thomas De Quincey said in On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth:

Here I pause for one moment, to exhort the reader never to pay any attention to his understanding, when it stands in opposition to any other faculty of his mind. The mere understanding, however useful and indispensable, is the meanest faculty in the human mind, and the most to be distrusted; and yet the great majority of people trust to nothing else.

If a character is on a mountaintop, we don’t write about our understanding of that fact. Instead, we sit with our character and write what we see, hear, and smell. A story is not us sharing our knowledge of what’s happening. We put ourselves into the moment, experience it, and write that experience.

Some of these changes can be made in extremely complicated ways that destroy and rebuild a story, but sometimes, it can be resolved with a few choice words, like moving from the general to the specific. Another (unrelated) word-choice edit is to watch for the use of the word “had”. Cut it unless it’s absolutely necessary, and if it’s needed, chances are, it’s only needed once. You can return to a simple past tense on the next verb.

Writers often say a character “had” done something, because they, as writers, are in a mental moment where the action is already done. They’re thinking the action is five seconds in the past, but in the story, the action is immediate. Your mental position within the story as an author is key to sharing the experience, but it’s also an imaginary construct that doesn’t really exist for your reader. It shouldn’t determine your verb tense.

That’s an abstract idea but really important. Keep your action immediate wherever possible.

The “had turned” problem is a past tense issue. In present tense, instead of translating to “has turned” the problem often shifts to “is turning.” Cut “she is turning” and write “she turns.” More to the point, you can survive doing this once, but it’s an addictive construction, and present tense stories become a thicket of “is turning,” “is seeing,” and “is smiling.” Soon, the reader “is pulling his hair out.”

As I sit with this final, beautiful story, I want to send a note to the author letting them know that one detail is repeated twice, and it’s a repetition that doesn’t work. Also, there’s a direct statement of the character’s revelatory understanding that can be cut. The lines that follow will reveal the same information in a way that allows the reader to discover the reveal for themselves. Otherwise, this is really good and has all the points we’ve discussed so far—except, many of the strong endings are twists, and this story’s twist is stated in that “revelatory knowledge.” The rest of the story if the emotional impact of that reveal, which makes it that much more important that the reader not be told before they’ve discovered the truth for themselves.

The story, though, is really well done.

— Thaddeus Thomas

Read my essays on Prose Style and Literary Theory here.

The book version is coming soon.