The Shortcut to a Better Fiction Style

The most important lessons to help kick start your growth:

From the Prose Style series:

This is a free post, but even with the paid-subscriber-only posts, you don’t necessarily have to pay to become a paid subscriber. (Subscriber Specials)

Talent isn’t everything, but it probably got you started down this road. That’s the way it was for me, but there’s a problem;—fiction requires a broader array of skills than people realize. The talent that gives you a taste for this, it only covers so much. It only takes you so far.

We have to hone our skills, and many of us have lacked instruction in the areas where we need it the most.

This essay isn’t about storytelling but about getting the story down on paper in the most pleasing way possible. It won’t cover everything, but it will hit the areas I believe to be the most important for a writer struggling to improve.

But let’s take care of some business first—in 4 parts:

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

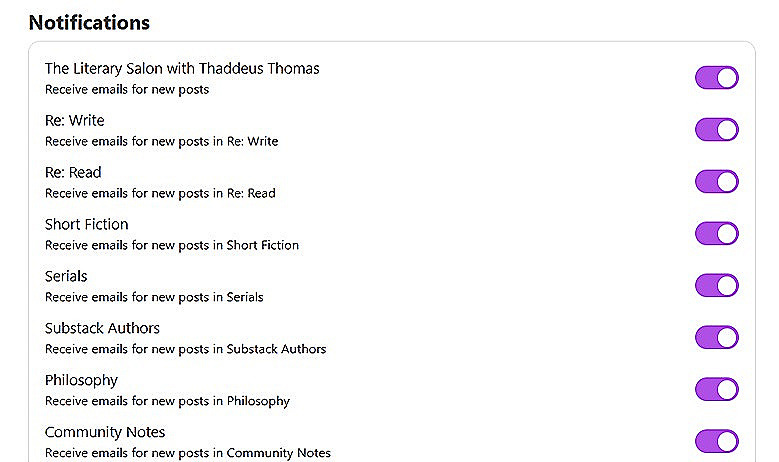

Every Section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

That’s https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Visit the Totally Awesome but Very Humble Authors promotion.

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only.

Now let’s talk about writing better right now

"Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style."

Kurt Vonnegut

I’m here to teach you games with language, but Vonnegut is right.

To go with that passion, you need truth, and while it’s beyond the focus on this essay, I recommend Writing Truth Through the Lies of Fiction to understand how we express truth in fiction. Follow that up with Show is Tell: Anais Nin describes Paris and finally Putting Zing into Your Long Action, which I’ll touch upon later in the essay.

Today, though, we focus on prose style which has become my venue largely because there’s a void of instruction for anyone but beginners. My intent is to approach this with you as one student sharing his learning with another, but that doesn’t mean I’m without claims to justify my efforts here.

Twenty years ago last month I founded the online critique forum Better Fiction and ran it for five years. In my time as a teacher, I’ve taught English and writing, and most importantly, I’ve struggled to grow as a writer of fiction. Maybe the struggle isn’t much of an honor, but its the truest one I have to offer. Otherwise, in 2007, I received honorable mention for The Sphinx and Ernest Hemingway in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, 20th Annual Collection, edited by Ellen Datlow, and that’s about as far as it goes.

Because the substance of what we say is so important, it can be easy to overlook how we say it—but the end result of doing so is dissatisfaction. We look at the sentences we write and feel like pretenders and amateurs, and worse than that—we fear editors will never see how great our stories are because they’ll never get past the prose.

To date, I’ve written 22 essays in the prose style series and begun two other series besides. That much material can be daunting, and I decided we needed a single essay to get you started and to help you see immediate improvement.

The Shortcut to a Better Fiction Style

When you read the three pieces recommended above, you’ll have covered truth, the reality of “showing” in fiction, and the cumulative sentence. That last one is especially important when it comes to the steps we can take to quickly improve our writing. It’s something I’ve touched on before in other essays, and it’s a good place to begin here.

The cumulative structure you first want to master opens with the independent clause and is followed by a series of adjectival phrases—most often with an action verb ending with -ing at the head of the phrase.

Rupert stood at the edge of the building, holding the brick in his hand, studying the throng of people below, knowing he could do nothing more than to draw their attention away from her and upon himself, bringing them crashing through the doors and up the stairs. There would be nowhere to hide.

The beauty of the cumulative sentence is how quickly it moves and how easily it presents itself as different from the standard sentence structures.

I cover the cumulative sentence in more detail here:

Putting Zing into Your Long Action, “Sentenced” to Life, and Aping the Style of Classic Authors.

In The Secret of Literary Style, I lay out my theory for what distinguishes a literary prose style and the alternative, what I call a “balanced” prose style. Literary style is about tension and release within the prose itself.

The balanced style calls for us to do the expected and follow the rules. Tension-and-release is about setting up an unsustainable pattern and providing release through change or completion. Some of these rule-breakers may be signature moves that define your style, but often they’ll be temporary flavors, used to heighten a passage, perhaps never to be used again.

The follow up essay that expands on these ideas is The Secret of Style: Part 2.

Movement and flow. These are two different ideas with similar results.

Movement I most recently addressed in The First Pretty Horse Ain’t So Pretty. Cumulative sentences work because they facilitate movement within the sentence. We can stop that movement, however, and one way this happens is with a complex subject. If it takes ten words to express the subject, your sentence isn’t moving for those ten words. Keep the subject simple.

Flow is about the reader’s ease of transition from sentence to sentence. One of the essays where I address this is Word Order and Reclaiming Passive Voice, but the standard advice for flow is to begin a sentence with the known and move into the new material. If you need to break flow, that’s one of the purposes of a paragraph. With that white space, the reader is prepared, but if that break falls in the middle of paragraph, the reader is unsettled and taken out of the story.

One area where writers often break flow is in their attempt to move from a more withdrawn POV to a character’s internal thoughts. The simplest solution is to make the thought its own paragraph.

In Simile and Cormac McCarthy Similes with You, we come to two major conclusions about similes. First, similes are an emotional comparison, not a literal one. Second, use mundane similes for lurid descriptions and lurid similes for mundane descriptions.

See what other essays I have to offer:

Understand and use rhetorical devices

The impact of rhetorical devices on your writing can be nearly criminal. Failing to use them when appropriate often makes it sound like you can’t quite get your wording straight.

I’ve previously referenced polyptoton in James Baldwin and the Long Sentence. It’s when you use the same word in two different parts of speech—or two different words derived from the same root. An example would be: I planned to make a plan.

Diacope is repeating a word after a brief interruption. Brief, I say! It’s what makes political jargon catchy, whether you agree with the idea of not, as in: drill, baby, drill!

Hendiadys is one I haven’t covered before, but it’s when you turn an adjective into a noun to accompany the noun it otherwise would have modified. If the sentence might have been, I endured the chaotic classroom, now it becomes: I endured the chaos and the classroom.

An isocolon is two phrases of parallel grammatical construction, as in: the men drove the mustangs; the women drove them to it.

A good book for the study of the devices is The Elements of Eloquence by Mark Forsyth. Among my essays, I cover the subject in Undressing Figures of Speech.

Finally, wherever you are in the writing journey, remember this truth from Anne Lamott and her book Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life.

"Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere."

—Thaddeus Thomas

Looking for more fiction writers on Substack? I’ve started a list of recommendations:

... Adds The Elements of Eloquence to my Amazon List (which is so long if I try to scroll it all the way down it crashes Chrome.)