From the Literary Theory series

Let’s clear the table: write what you know is great advice.

When Hemingway told himself to write one true sentence, he was saying the same thing. You can write science fiction and fantasy and tell the truth, and you can write auto-fiction and lie through your teeth.

Today, we talk about truth.

But let’s take care of some business first—in 4 parts:

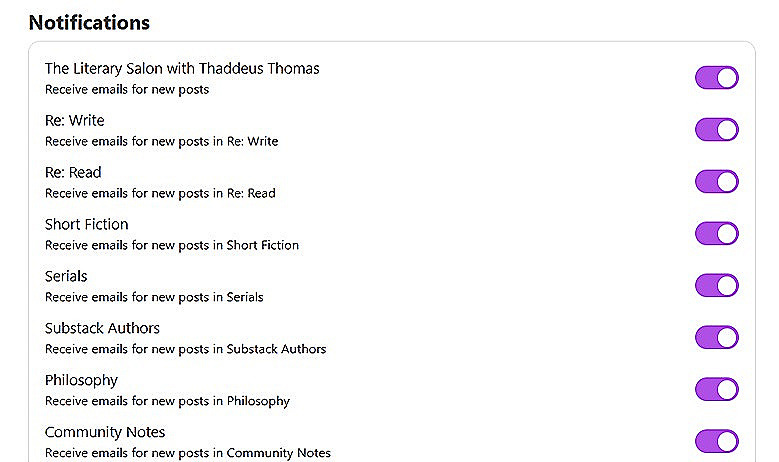

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

Every Section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

That’s https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Visit the Totally Awesome but Very Humble Authors promotion.

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only.

Now let’s talk about Getting Real

“All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway told himself this when he was having trouble writing. “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know.”

Wonderful self encouragement—only how do you do it? How do we write anything and tell the truth? What is truth?

Can we handle the truth?

I considered calling this essay The Importance of Being Ernest Hemingway, but I didn’t. It’s not about being him or writing like him.

Fundamentally, this is one of the secrets to great fiction, a secret highly gifted writers can forget:

Writing Truth Through the Lies of Fiction

As a teacher,1 I learned that my most gifted writers often tried the least. They expected to bulldoze me with their prose and failed, while the students who struggled put their hearts into the work and often turned in the best assignments. Talent isn’t enough. Perfect prose isn’t either.

The substance of our prose must have substance.

When I said my students “put their hearts into the work,” it’s not sufficient to interpret that as mere effort. The better body part for that would have been the back—but perhaps the phrase means little because it’s trite and cliche. Maybe I thought it was enough to bulldoze you without putting in the effort and coming up with something that said what I meant.

The students who struggled knew instinctively that the only way to impress me was to find the depth of their subject and explore it—so that what they wrote did more than convey factual accuracy, it conveyed something I could relate to and see exemplified in my own life, forcing me to reconsider old assumptions and come to new insights about my world and who I am within it.

We have a name for that something. We call it truth.

You can convey that truth no matter how fantastic the world or its characters; truth isn’t chained to the details that describe it. It’s revealed through specificity, but once revealed, it speaks, no matter how different our circumstances might be.

With truth, writers give life to stories where other writers have fallen flat, and if you’re asking how, the answer is simple:

Write what you know.

See what other essays I have to offer:

“Write the truest sentence you know,” Hemingway said. He didn’t say write the truest sentence that ever existed, just the truest you know.

Write What You Know

The mistake is to think the only way this advice works is to write like Harper Lee with To Kill a Mockingbird. Maycomb is based on her childhood in Monroeville, and Scout is practically the author. This is writing what you know on a story-inspiration level, but that’s not the only way to do it.

J.R.R. Tolkien birthed modern fantasy from his work as a philologist. In fact, it’s said that he invented a language and then created a world where it could feel at home, but neither of these examples are what interest me the most for this discussion.

Tolkien also exemplifies the advice when he draws from his experience in World War One, and that gets closer to a more universally applicable approach. We’re not always going to write about something that’s directly inspired by our own lives or fields of expertise, but we can see how our experience applies to our subject and write from that place of knowledge.

It may be that the greatest impact is found in those experiences we dare not talk about in any other way.

Right now, Literary Salon is engaged in a reading of Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses. (There’s still time to get started. So far, I’ve only written about the first paragraph.) In this context, I want to bring up the revelations from that Vanity Fair article.2

Augusta Britt3 saw herself in that book.

And I remember thinking to myself that being such a lover of books, I was surprised it didn’t feel romantic to be written about. I felt kind of violated. All these painful experiences regurgitated and rearranged into fiction. I didn’t know how to talk to Cormac about it because Cormac was the most important person in my life. I wondered, Is that all I was to him, a trainwreck to write about?4

Why that example? If I’m going to bring up the subject, why do it in this context?

It’s rare that we get this clear an example of someone drawing from secret experience and knowledge.

In the book, when John Grady tells Alejandra about his time in prison, she’s taken aback:

"How do I know who you are? Do I know what sort of man you are? What sort my father is? Do you drink whiskey? Do you go with whores? Does he? What are men?"

Cormac McCarthy

It feels pertinent.

If the questions Alejandra struggled with are the questions his readers are asking now—I suggest they were first asked by McCarthy of himself. It’s possible he might have been thinking of something Augusta Britt said, but as he worried about being arrested and later, as he warned Britt that it was inevitable people would find out, I suspect he was wrestling with what sort of a man he was.

All The Pretty Horses might not have been conceived to be about McCarthy and Britt, but it’s still about them. It’s about her. The biographies of Augusta Britt and Alejandra Rocha y Villareal are not the same. The facts are different, but shared truths still found expression.

There are facts in the book that are easier to get right because McCarthy knew them from experience or study;—writing what you know can help that way. It can help you share the little details others will miss. All of that’s important. Use it where you can.

However—

The true power is in exploring your truth through the story’s characters. Make it uncomfortable. Hemingway might have said, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”5 Whoever said it or said something like it, this is what it means—the best stories are written with truths that make the author squirm. They’re written with our pain and regret. Nothing great is born of wish fulfillment but rather of broken people confessing their sins and sorrows through fiction.

Fiction is a priest who takes his vows seriously. He keeps your secrets.

All you have to do is sit down at the computer and squirm.

—Thaddeus Thomas

Looking for more fiction writers on Substack? I’ve started a list of recommendations:

End Notes

I decided this needs a footnote. I was a school teacher for about five or six years, but the episode that best exemplified this was after I’d left the school but was teaching a English class for home-schooled seniors in my spare time. None of those details are important.

If you have no idea what I’m talking about, the Guardian wrote up a summary. Frankly, the url is a pretty good summary on its own. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/nov/20/cormac-mccarthy-began-relationship-with-16-year-old-while-42-and-married

Excellent essay! Write what you know is always taken too literally, especially by the proponents of auto fiction. And about that quote, I’d always heard it attributed to Red Smith, and that was before the Internet made it impossible to know who said anything.

Food for thought: I'll admit that what you're addressing is literary fiction, which is different from the King/Clancy/Patterson school of hack writing, but I wonder ...

While it is true that even the most fanciful world a writer creates can/does contain "truths" or their bleeding hearts, does every book one writes or reads have to contain accurate philosophic or gut-wrenching observations of the human condition? Writing about only that which a writer knows or experiences means s/he's already limited h/her imagination. Orwell knew about Fascism and Communism, but he lived in a world before the advances in technology made his hell-on-earth totalitarianism possible. Yet, he could imagine and a possible future course of reality ---he does not, however, imagine how we 2025 folks can prevent and/or destroy such a world with practical advice. Why? Because he's not living in 2025. He doesn't know about Trumpism and the current dismantling of the tyranny of the administrative state. It's much the same Max Weber who wrote about the iron cage of bureaucracy, and the disenchantment of the universe. It's the same for Jules Verne, DaVinci's drawings, and H.G. Wells.

I hope the writer of the Dexter series has never killed anyone. And Ben Hur is fiction, too, albeit inspiring. Did Cecil B. DeMille actually see Moses part the Red Sea? I know enough about government to know it's bullshit, but I'm also a patriotic American.

I understand what you said about your students. Some take their studies seriously and others don't. Some struggle to add 2+2 and come up with five, write it down, and the world calls it genius. Creative writing is different from academic or business communications or legal briefs or how-to build better mouse-trap books because it doesn't have to be the product of what people know .... enter the Jabberwocky. I would suggest that most American creative writing limits itself to the internal/subjective/idiosyncratic approach to truth rather than the external/objective/universal, and that's why more people write than read. Those that do read fiction, develop a cult of personality, or genre, i.e. become fans of a person, rather than objectively evaluate content and, as you address in your superlative essays, style.