I’m turning these essays into a book, and this post is filling a gap with a needed new chapter. The book is long enough, but I want to make sure I cover everything I want to cover and not assume I’ll have the opportunity for a follow up.

With that in mind, we turn our focus to the work of Gerard Genette, and we’ll begin with rhetorical metalepsis which is comparable to metaphor or metonymy in that it uses a creative and indirect reference to convey an idea.

It isn’t very helpful to compare anything to metonymy since we haven’t covered it yet. Let’s start there instead.

Metonymy substitutes a word for a concept closely related to it. If I say Hollywood, what do you think of? American filmmaking, most likely, because we reference that district in Los Angeles to refer to the entire industry. That’s metonymy.

On a rhetorical level, Metalepsis is similar but the connections are creative and indirect. When we refer to someone going into the lion’s den or opening Pandora’s box, we know those terms stand for other concepts like danger and compounding troubles. It’s not a metaphor or metonymy. Genette called it metalepsis.

These examples lack power because they’ve become cliche, but metalepsis can be creative. Let’s dig into it!

But first, let’s take care of some business—in 4 parts:

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

Every Section has a toggle. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

This is part of The Re:Write Series.

To choose which series come to your inbox, go to:

https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

If you have a complimentary paid subscription that’s ending, if you do nothing it will revert to a free subscription.

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

3. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only, and I have a special in place until I reach 100 paid subscribers. You’ll keep that discount for as long as your hold the subscription.

4. Preview select chapters from my WIP:

Deeper Stories: a Fiction Writer’s Guide

I’m turning these essays into a book, and you can grab a draft sample when you subscribe for free. (Available to current subscribers, too.) I’ll be announcing pre-orders for the whole book soon!

Free for new and existing subscribers. Learn more here:

Now, let’s discuss: metalepsis.

Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot. Snotgreen, bluesilver, rust: coloured signs. Limits of the diaphane.

—James Joyce, Ulysses

Metalepsis is a more recent concept that most anything else we’ll study. Gerard Genette introduced the concept in 1972 in his book, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, a foundational work in narratology, the study of narratives and the mechanics of storytelling.

When Stephan Dedalus thinks, “Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot.” what does signatures of all things mean? It draws parallels to the doctrine of signatures, a pre-modern belief that objects bear visible signs of their spiritual nature. It’s metaphysical and philosophical and brings with the allusion all those layers of suggested meaning. That’s rhetorical metalepsis.

Sure, Thaddeus. Like we’re going to recognize a reference to some ancient doctrine. We’re never going to use this, are we?

Chances are, you use it in real life, and once you recognize that, it will be easier to transfer into your fiction. In life, these instances are often pop-culture references. We have our favorite movie quotes, and some of them work into our daily speech with friends and family. When they’re used often enough, fragments of the quote begin weaving into our speech.

Perhaps when you or your child was young, you saw the movie Horton Hears a Who and fell in love with the quote, “In my world, everyone's a pony, and they all eat rainbows and poop butterflies.”

Years later, instead of saying, “Have a good day.” you could be telling one another to “Poop butterflies.”

Do that in fiction, and you have metalepsis.

Perhaps your character’s stream of consciousness reports him feeling like “another brick in the wall.” You don’t have to explain the connection to the Pink Floyd lyrics; it’s just there, carrying layers of meaning for those familiar with the work.

In fact, explanation removes it from the realm of metalepsis and drops it into the NCIS syndrome where every reference has to be explained so no viewer is ever left out. Prose gives us multiple ways to pack meaning into small spaces, and readers aren’t lacking when some of that meaning is missed. They’re not meant to grasp everything, and their experience isn’t deeper when they do understand a reference. It’s merely different, and each reader’s experience is informed by layers of meaning that will be unlike the layers of meaning brought by someone else, unless you really make an effort to keep your storytelling on a surface level.

The more you worry about whether people will correctly interpret your story, the more sermon-like the story will need to be, but the interplay of the reader and your text creates something new. There is no correct interpretation. You had your meaning in mind as a writer, but I don’t put much value in that.

My recent story, Such was the Epiphany of Theodore Beasley, includes a good deal of my personal philosophy of how emotions and memory work, and they’re given voice by the character of the prison counselor, who I see as a well-meaning man who’s frightened of his job. Yet, one reader commented that the counselor should be shot! Clearly their understanding of the story is different than mine, but it doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Your understanding of a text only becomes wrong when you turn it into a Youtube video about what Stanley Kubrick really meant when he made The Shining.

Snark aside, what I mean by that is there’s a difference between a personal experience of a text and public interpretation. Public statements are subject to scrutiny where misreadings and logical fallacies are pointed out, but it’s also where legitimate meaning is lost because another reader lacking your layers of meaning will accuse you of “reading something into the text that isn’t there.” Great Caesar’s Ghost! Have we completely lost the idea that we’re supposed to read into the text? Stories can be much more interactive than we give them credit for, and this concept should be key to the generations growing up with video-game storytelling. Stories don’t just have to be something you consume. Techniques like metalepsis are Easter eggs that allow the reader to connect the story with prior knowledge and experience. You might miss one and not understand the reference of another, but the third could speak to you, perhaps in ways the author never imagined. They create openings for the reader to act as a story’s co-author, and those connections are powerful neural pathways that increase our emotional response and the story’s personal importance.

Hold on, Thaddeus. You said these layers of meaning don’t create a deeper understanding. That sounds pretty deep to me.

We’ll all connect differently to a text based on what we bring to it. It’s easy to think the connections we make are the true beauty of a story, and the experience of others will be diminished unless we instruct them thoroughly. It ain’t so. I had a roommate like this years ago, and his explanations never made me enjoy a story more—thank you very much. You’ll see the same attitude in online narrative discourse today.

We can share our personal connections to the text, but we need to avoid couching those connections as being the full and better experience.

Discover all my essays on:

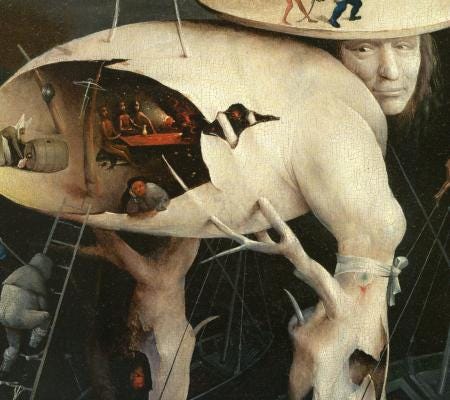

Ontological Metalepsis

I picked up Chuck Palahniuk’s Choke at the library today and then left it in my daughter’s car. While it was still in my possession, I managed to read the first chapter, and it blurs the distinction between fiction and reality. The narrator, the main character, is speaking directly to me, telling me not to read the book. Eventually this is given context with the book being a journal he has to keep as part of his 12-step program for sex addicts.

That fourth-wall breaking metafiction is the ontological level of metalepsis. We see it in action when a narrator steps into the story, when characters interact with the narrator, or when the story acknowledges its own artifice or communicates directly with the audience. Think of the movie Stranger than Fiction.

The book and movie versions of Princess Bride use different framing devices which are both examples of metalepsis, whether it be the author William Goldman’s fictionalized self editing the manuscript of the story he’s telling or the narration by Peter Falk interrupted by discussions with his grandson.

Meta: a self reference; Lepsis; to seize.

I used ontological metalepsis in the section above when I had the reader complain directly to me that we’re never going to use metalepsis.

Poop butterflies,

— Thaddeus Thomas

Weekly Flash Fiction for Paid Subscribers—these won’t be emailed to you, but you’ll find the link in my regular posts. Here’s the beginning of a flash serial: Forgotten Blood.

Always glad to learn new terms. I knew what you were talking about, but never knew the name of it. I did, however, expect a reference to Metalica, Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, or Motorhead or .... Leo Sayer, who made Megadeath a real possibility.

One of the harder things I had to do when writing Tranith Argan is to rid my writing of any modern reference or anything that would ground the story to our world. So not only could I never use “Great Caesar’s ghost!”, I couldn’t even use “out of the frying pan and into the fire.” I had to make my own variations of phrases and concepts, but it’s hard because we say such things all the time.