Bonus points to anyone who identifies the reference in the sub-header above.

From the Literary Theory series

This one doesn’t come from the masters. It’s mostly me, and I’m speaking to writers on Substack—mostly literary—about a choice we’re making that undermines our fiction. Balanced writers (genre writers) aren’t off the hook, though.

But let’s take care of some business first—in 4 parts:

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

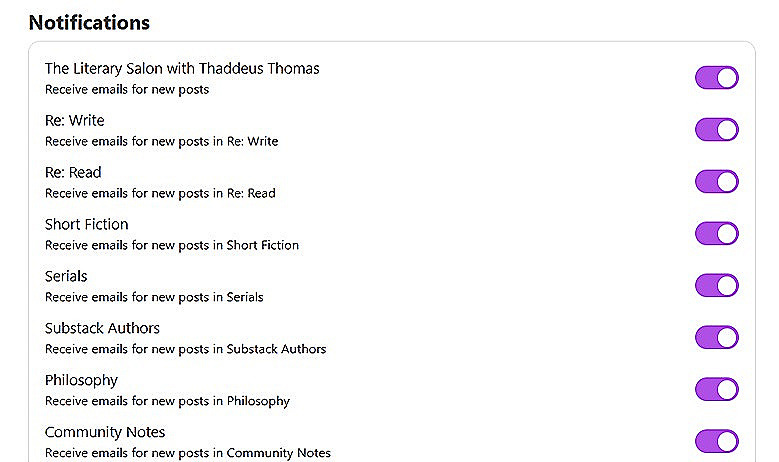

Every Section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

That’s https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Visit the Totally Awesome but Very Humble Authors promotion.

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only.

Now let’s talk about choices

“You must ground the reader with the Ws—who, when, where, and what.”

writing coach Teresa LeYung-Ryan

This isn’t about a rule. The quote suggests otherwise, framing it as something we must do in order for the reader to feel invested in our stories. Literary fiction is often about breaking these expectations, and the author challenges himself to capture our attention with no clear idea of the specifics of a situation. The writer succeeds, and we’re caught up in a personal psychology that may very well be our own without knowing much at all about who we are or where or why.

And the story is read and loved and imitated—sometimes without understanding why the choice was made or how it was made successful. That’s okay. That’s actually very much okay. We can come to our deepest understanding by attempting to employ techniques we don’t understand.

But it’s a choice that’s made often, this ungrounding of our fiction, and I think we need to consider what connects us to a story beyond the beauty of the language. It’s a cliche to say if one sense is lost, we learn to use the others more intensely, but it’s a proper metaphor. In most cases, the answer to losing one W is to strengthen another.

Note: I don’t write these essays just for literary writers. Anyone can employ the techniques we talk about. This time, it’s the literary writers I’m taking to the tool shed. Everyone else can watch, giggle, and pick up whatever lessons apply. Balanced writers will find occasion when they, too, cut loose a W, but you’re far less likely to do so without cause.

This may not be your problem, but you still need this solution.

The Best Short Story Ever Written

Hey Baby got caught writing a letter to his girl when he was supposed to be taking notes on the specs of the M-14 rifle. We were sitting in a stifling hot Quonset hut during the first weeks of boot camp, August 1966, at the Marine Corps recruit Depot in San Diego. Sergeant Wright snatched the letter out of Hey Baby’s hand, and later that night in the squad bay he read the letter to the Marine recruits of Platoon 263, his voice laden with sarcasm. “Hey, Baby!” he began…

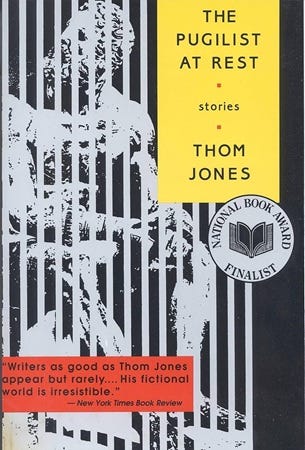

Thom Jones, The Pugilist at Rest

The Pugilist at Rest is the best short story ever written.1 Don’t contradict me. That’s just fact, and there is no alternative.

The story was first published in the New Yorker Magazine in 1992 and was collected in a couple different “Best Of” collections, which is where I discovered it. In 1993, it was the title piece in his collection of short stories, which I also bought, and which I no longer have—neither that nor the Best of American Short Stories that featured it. I also owned the O. Henry collection in which it appeared.

In the intervening years, we went through a period where my wife suffered severe skin allergies, and I had to give up most of my books. A damn shame.

That personal collection was nominated for a National Book Award. I should buy another copy, but if I do, it will be for that one story. When they say “lightning in a bottle,” that story is what they mean, and the entire literary world felt its jolt. After that, he appeared in the best places frequently, and Esquire called him a virtuoso of the short story. For me, though, he only ever wrote the one story, and that was all he ever needed to write. God rest his soul.

The story focuses on Hey Baby, but you know the narrator is an active character… “We were sitting in a stifling hot Quonset hut…” and you know they’re both newly recruited Marines, in 1966, undergoing basic training in San Diego as part of Platoon 263. The information itself is in character because these are details a veteran would note. He doesn’t stop to tell you:

Quonset hut: (n) a lightweight prefabricated structure of corrugated galvanized steel with a semi-circular cross-section,

…because it’s natural knowledge for him and he expects you to know it. He doesn’t just say “our platoon” because other Marines will want to know what platoon. They might have known men in the same unit.

The Pugilist at Rest opens as a textbook example of grounding the reader in all the W’s, but that doesn’t mean it’s the only way to do it. What it shows us, however, is that a great literary work can ground its reader without losing sophistication. You don’t have to suspend your reader in space simply because that’s what literary writers do. It’s a choice, and if you make that choice, you’re going to work hard to earn it.

See what other essays I have to offer:

Writers Share Their W’s

Some stories jump into a stressed mind with no tether to character, time, or place, and in the short term, it’s not too hard to pull off. All it takes is distraction. If the grounding is to be sprinkled across early paragraphs, the distraction only has to last so long, but how do we sustain such an effort and not lose the reader?

Well, point number one of this article is we should think twice before jumping on that trend. When these stories are successful, part of the draw is the novelty, but novelty doesn’t last. That’s not to say we can’t do it. Just talking about it here with any attempt to dissuade you is probably inspiring some of you to try—so let’s look at how we succeed.

Success in fiction is centered in maintaining the reader’s interest, but we’ll start by looking at that distraction I talked about.

Wonderful prose or a great hook will buy an author time. Jeopardy or the promise of reward are good hooks;—that’s violence and sex in the vernacular. A hook only lasts so long, though.

It’s probably literary sacrilege to say prose only gets you so far. The prose is supposed to be all that matters, and with my entire Substack personality being about prose style, I need to be leading that parade!—but I’m not.

To hold the reader, you must entertain them, and the first rule of entertainment is change and contrast. There will be a unifying form and sense of style to a piece, but within that, there will be room for change and contrast. Certain schools of fiction allow for limited scope, but even if your entire story is internal, room remains.

A character arc is about change and contrast. Setting becomes significant in how it contrasts with other settings in the story. You get the idea, every component is about contrast and change, and when you have every component engaged, your story drips with change. For every W you remove, your story runs the risk of becoming more monolithic.

If you narrow your W focus, consider your story’s growing need for variation, which you may have to meet with heightened contrast and rapid change.

When we talk about structure, that’s patterns of change and contrast with a goal and sense of direction and of progress. Throw out all the details of structure, but retain at least these. Give us a goal, either real or false. Give us a sense of direction, either toward the goal or not, and give us a sense of progress, that we’re going somewhere, even if it’s the wrong direction.

If you want a list of the usual suspects [for how to keep a reader’s interest], go ask ChatGTP. My argument is that every component you allow in your story has an integrity that needs to be respected but which allows for contrasts, and these contrasts reveal the integrity rather than undermine it—until it is intentionally undermined or otherwise changed.

And too often, when we remove the W’s, we’re left with a monolithic mass of beautiful prose, generally with a sense of progress, but not much more.

The Best Short Story Ever Written: Part 2

According to the New York Times:

Jones was 47 and working nights as a [high school] janitor… when he mailed, unsolicited, a fictionalized Vietnam War story to The New Yorker. It was admired so immediately that it bypassed the usual vetting by multiple editors and sailed into print in late 1991, receiving critical acclaim, and the O. Henry Award.

If you’re interesting in reading The Pugilist at Rest, LitHub has it available for free.

—Thaddeus Thomas

Looking for more fiction writers on Substack? I’ve started a list of recommendations:

Listen here sir, I'll have you know that I can read definitely lose a reader in much less than 10 sentences. Give me 10 words. I'll make the magic happen.

I really liked this. I've got nothing more to add.

Actually, one thing. I feel with short stories you get two paragraphs to get the reader involved, maybe three. Novels there's a bit more investment but short stories can be dropped and moved on to another bite sized fiction way quicker.

That said, the story you picked does it in one paragraph so yeah, it's very good.