From the Prose Theory series:

Lets meet Ren Powell:

Born in California, Ren has (somewhat) settled on the western coast of Norway. She has published six full-length poetry collections, over a dozen books of translations, and her playtexts have been performed in Canada, Norway, and the United States. Ren’s own work has been translated into eight languages.

Ren currently writes, and teaches theater at Vågen Upper Secondary School for the Visual and Performing Arts. She holds a Ph.D. and an MA (with Distinction) in Creative Writing from Lancaster University (England), and a BA in Theater Arts from Texas A&M University (USA). She has diplomas in teaching and counselling from UiS, HiL, respectively (Norway). A member of the Norwegian Author’s Union, the Norwegian Guild for Drama & Theatre Instructors, and the Dramatists Guild (US), Ren also served as the International PEN Women Writers’ Committee representative for Human Rights from 2006 to 2008.

She is the currently the Poetry Editor for Orange Blossom Review, and an associate editor and feature writer for Poemeleon. Alongside her teaching at Vågen, she mentors writers of all ages—in English and Norwegian—offering guidance and inspiration.

But let’s take care of some business first—in 4 parts:

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

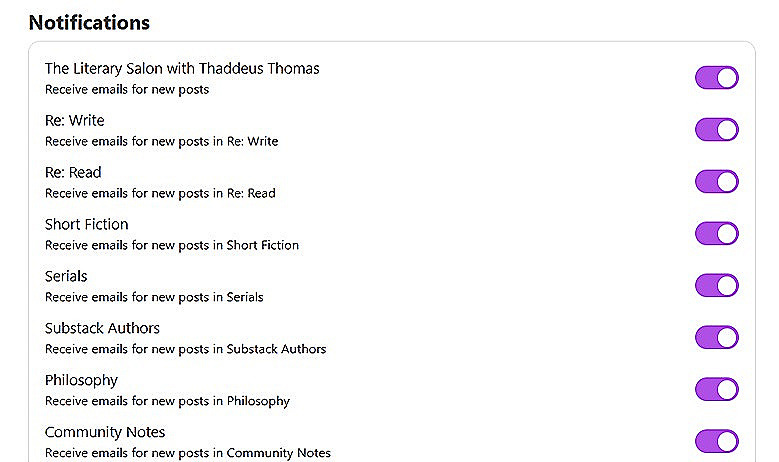

Every Section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

That’s https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Visit the Totally Awesome but Very Humble Authors promotion.

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only.

Now let’s hear from Ren Powell:

“The purpose of playing... is to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature."

Shakespeare

The Platypus Ain’t Got No Genre

I have to admit that a part of me still baulks at putting a mobile phone or a Dairy Queen Dilly Bar in a poem. It’s because I first felt the pull to write while reading the poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. If the poetry I was reading wasn’t unequivocally Romantic, it was Modernist, and inscrutable. But as a preteen, a teen, the classics and the limited choice of styles they represented served as prescriptive models to emulate. The idea was to write timeless literature, and it was a long time before I understood that the classics’ timelessness is a myth.

In my teens, I was also reading Stephen King and dozens of sci fi writers, but in my mind if you wanted to be a great writer, you wanted to be Jane Austin not Judy Bloom. I thought style existed as a hierarchical measure that verified quality. I know it looked like snobbery. Manifested as snobbery. But I was tuning into the music of the canon, I was being a good student.

I was in college before I read King’s novelette The Body. Until then I’d thought of him as a fabulous storyteller: sentences were a matter of utility. But when I neared the end of The Body, I was in awe of the tension in my own body, the way the language held me despite the fact that no girl was going to set anything on fire or kill the monster. I realized that the spectrum of storytelling and the spectrum of style weren’t discrete, nor were they hierarchical. Despite what my English teachers told me. It was freeing—as a reader, and as a writer.

I’ve had editors tell me they want to rewrite my work, to help with the flow. Often, what they wanted to do was rewrite my work to suit their editorial style. I don’t always mind, often my writing could use a bit of a scrub. But honestly: controlling the flow is an element of style, not an error.

Hell. I may not want readers to “flow” unobstructed through my text.

Did you see what I did there? Hell. Full stop. The vernacular is an element of style. It has its own powerful music. And my use of italics, which my instructors always discouraged as laziness or cheating, is just another orthographic tool to convey the writer’s intent. Like a full stop. Or an em dash. Or letters that make up words.

There have been times when I wonder if skilled writers object to new styles because they are winning at the game under the current rules?

Often, what editors (or ChatGPT) call flow or “readability” in a text, is really skim-ability. The familiar music. We’re taught to write our sentences with the same easy-going, let’s-not-upset-anyone elevator music. No discursive details, use generalizations. This is why we use the passive voice too often: it is easier on the ear. Iambs fall naturally into place in the passive voice, plosives are neatly muffled by soft vowels. It’s pleasant to listen to.

Sometimes we do want to be soothed—but there are times when we don’t want our sticky, spiky characters to be seen (or read) with the protection of kid gloves. We want to give the reader a full-on, immersive experience with the dangerous elements of the world. Have you met Alex in A Clockwork Orange?

I’ve been reading a novel by Rebecca Watson titled little scratch (Faber, 2020). When I first picked it up and flipped through the pages, I thought it was a poetry collection, or one long poem. To be honest, I’m not entirely certain what makes this a novel and not a poem beyond marketing needs. Many pages present as concrete poems, the shape or typographic presentation illustrating the subject matter. When the speaker (unnamed) is thinking about lurching back to bed, the words are spaced unevenly across the page.

Other sections involve the use of columns and competing text in this stream of narrative. The resulting, almost hyperreal narrative of the self commenting on its own awareness feels true, and I’m confident the frustration it causes the reader is intentional. I either race down the page, then return to read the other column, or I attempt to read across the page while keeping the two narratives separate in my mind—almost like dealing cards for two players.

This isn’t an unfamiliar technique in poetry. I’ve used it myself. But I’ve never seen it sustained this long, or felt it drive such a sense of urgency. I had to start the book three times, because it does need to be read at a sprint for the fragments of text to hold together. From the first page, we follow a woman from waking, to rising, to going to the bathroom (in surprising detail). We feel her emotional, visceral experiences without commentary. The character and I have very little in common, and her culture is one that I don’t have first hand experience of, but I am pulled into her experience.

It’s effective.

So I’ve been asking myself about this “style” of writing. The first person stream of consciousness is certainly nothing new. Neither is the abandonment of grammatical rules for the illusion of verisimilitude.

But is this literary? Is it even prose? Poetry?

When I teach theater genres, I always begin by talking about the platypus, this weird creature who defies categorization. Part mammal, part bird or amphibian, part reptile—with its venomous claw. Nature doesn’t evolve in neat little categories, and art doesn’t either.

Genre is a tool that helps us discuss art, not a mold for us to pour our creativity into. I think trying to analyze little scratch would be like dissecting a platypus. And if I am going to stick with that metaphor, I’ll say that it’s not a bad thing. When the British scientists were given a platypus, they were confounded by the furry, egg-laying, duck-billed creature, and convinced it was a hoax. They had to dissect it to appreciate what a wonderful creature it is.

It has its own style.

Not fitting into a genre is possible. But style is something we can’t avoid. It’s something we need to cultivate: our own style, and the ability to appreciate an unfamiliar style.

This or that style may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but it doesn’t need to be for everyone.

— Ren Powell

Wow! That sounds both terrifying and wonderful.

This is showing as if it's a paid post but nothing is set to paid.